We spent a few days in the Rockies last week, on a memorial trip for a family member we lost last year. We were surprised at what appeared to be low snow amounts, particularly up at the hydrologic apex of North America: the Columbia Icefield. When we arrived there on Thursday, the wind was howling and the slopes were scoured almost bare – dark brown and black rock showing through the thin dusting of snow. The icefalls on the Athabasca and Angel glaciers were exposed, their deep blue and crenelated crevices visible from the car park at the bottom of the glacier. Ravens hopped hopefully around the vehicle, puffing out their feathers as they glided in the onslaught of the westerly winds. Needless to say they waited in vain.

Data from Alberta’s mountain snow course network (see map – Columbia/Kootenay sites not included) indicate that snow water equivalent (SWE) across the 36 stations is currently averaging 103% of normal, with a range of 49-145% of average (see data here). The minimum and maximum values were located in the far southern Rockies and the far northern Rockies, respectively.

It would seem that our perception of low mountain snowpack was coloured by what we’ve seen in the previous couple of years – above average snowpack that dominated the landscape. However, since there isn’t a snow course at the Icefield itself I suspect that high winds this year have scoured away much of the snowpack in this location. Icefalls are rarely visible through the snow at this time of year…

On our trip home, we noticed that Southern Alberta had an even more severe lack of snow. The yellow-brown and white-yellow stubble of last summer’s crops stretched to the infinite horizon, broken only by fence lines marking the barbed edges of each farmer’s field. Pale yellow tumbleweeds stuck in the tops of the stubble, like clumps of hair in the bristles of a brush. Snow was only found behind the odd snow fence – and then in a limited swath of sculpted hard-pack, speckled brown and black with dirt from the prairie winds. In the area of last fall’s large grass fire, the snow was black with ash and dust. What little there was of it…

Because Alberta Environment & Sustainable Resources Development doesn’t measure snow on the prairies, I went to Alberta Agriculture’s maps of snow in stubble fields as of 30 January. They show an area of low snow concentrated around the southern end of the province.

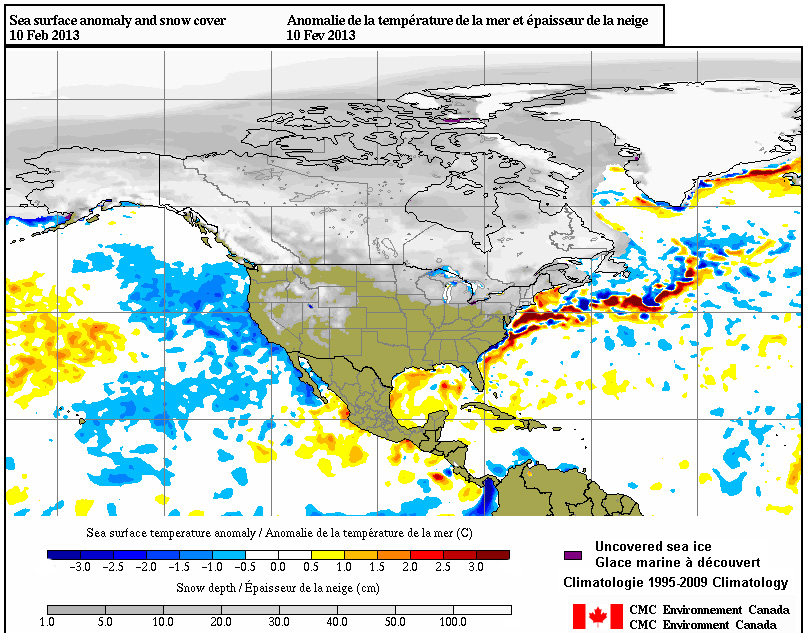

To double check these results, I also examined Environment Canada’s time lapse of snow cover extent for the past 30 days. On the still image from 10 February shown below, you can see the same strip in southern Alberta – close to the US border – that showed up in the Alberta Agriculture map as an area of low snow.

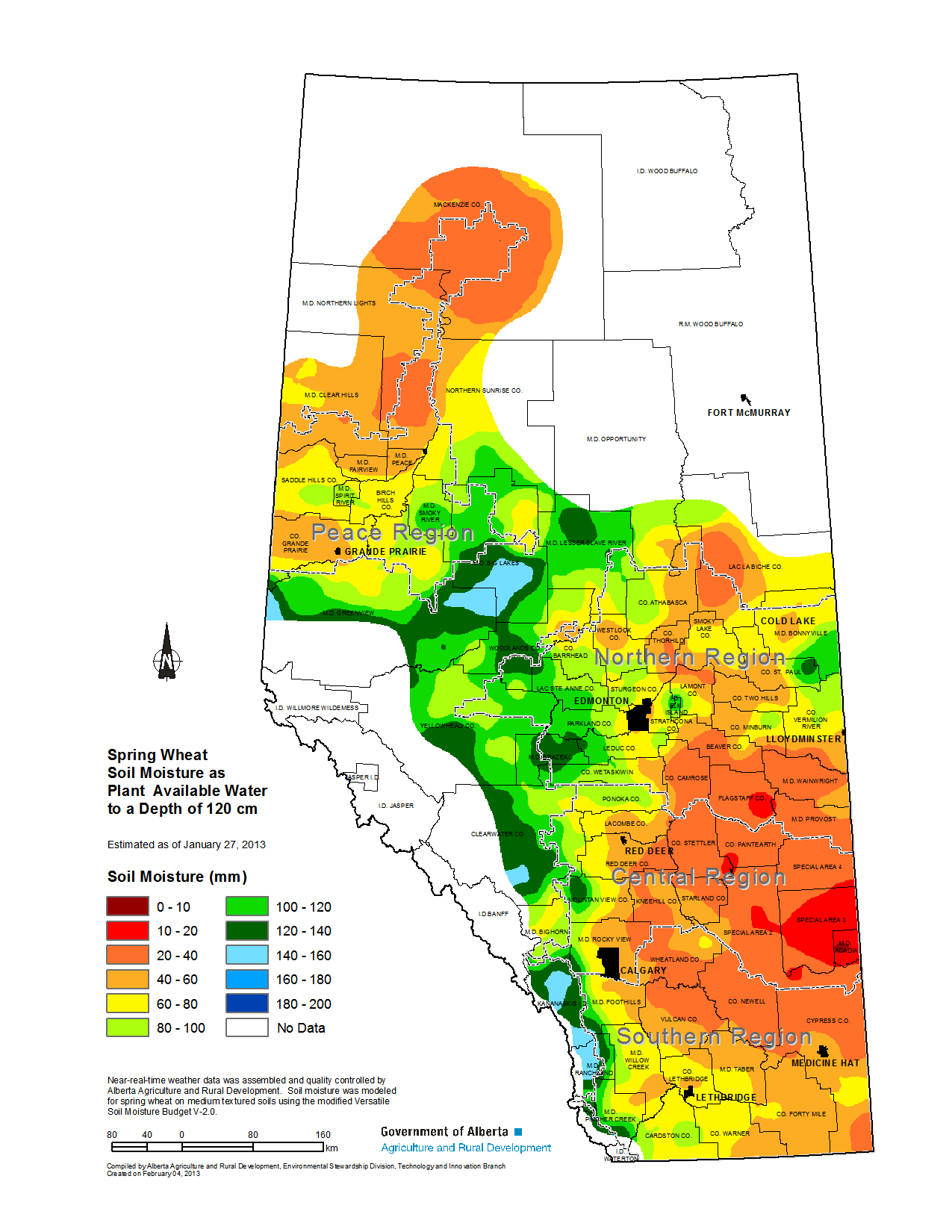

What we’re most interested in here is obviously soil moisture: will the low snow water equivalent in southern Alberta at this time of year affect our ability to grow crops in the upcoming summer? This is where the picture gets interesting, because it’s not only a factor of this year’s SWE, but also of antecedent moisture conditions from the years prior. So when we look at the soil moisture map from Alberta Agriculture (below), which models soil moisture for spring wheat across the province for 27 January, 2013, it suggests we might have a bit of a problem. Even more interesting, the central-eastern part of the province has a more serious soil moisture deficit – even though snow in that region this year is high normal to moderately high (according to the previous Alberta map above).

The two takeaways from this post?

- Memory is an unreliable indicator of relative abundance/depletion of snowpack – or other resources – on the landscape. This is similar to the baseline shift mentioned in my previous post.

- Soil moisture is related to seasonal SWE over a period of years – thus the relationship between the two in a single year isn’t as cut and dried as we might think it is.

I’m happy not to see any more snow down south, as it usually melts and refreezes causing a slippery mess! But for the sake of summer moisture, it might be just what we need.

The omega block that has been relatively persistent should keep down snow amounts in the next week or two. Columbia Glacier on the icefield could use the good snow

Columbia is likely getting more snow than Athabasca, being on the W side of the divide where systems have been blocked (covering Interior BC in a lot of snow). Athabasca is really suffering – surprised to see such thin snow cover on it this year.

Did anyone try to correlate soil moisture to seasonal SWE over a period of years?

Jan

Yes people have tried to do this, but it’s complicated by the effects of vegetation (both in terms of shading & ET).